England’s almshouses form a living link between the medieval past and modern social care. These charitable housing institutions, originally known as hospitals or “bede-houses” (from the Anglo-Saxon bede, meaning prayer), were established to shelter the poor, elderly and infirm, long before the welfare state. Over the centuries, almshouses have evolved under the patronage of monarchs and clergy, weathered the upheavals of the Reformation, and adapted to contemporary needs, all while preserving their core mission of providing “hospitality and shelter” to society’s most vulnerable.

Medieval Origins and Purpose

Almshouses in England date back over a millennium. The earliest recorded foundation is traditionally attributed to King Athelstan in the 10th century, and the oldest still-existing almshouse is thought to be St Oswald’s Hospital in Worcester, founded around 990. These early almshouses were usually established by religious orders or pious benefactors as acts of Christian charity. They were often called “hospitals” in the original sense of the word – places of hospitality – and served as sanctuaries where the poor could find food, shelter and spiritual solace. For example, St Oswald’s in Worcester was created by the bishop as a refuge where brethren would “minister to the sick, bury the dead, relieve the poor and give shelter to travellers” locked out of the city at night. Likewise, the Hospital of St Cross in Winchester – founded in the 1130s by Bishop Henry de Blois – provided permanent housing for “thirteen poor impotent men” who were so weak that they “rarely or never” could stand without help, and also offered a meal to 100 other poor men at its gates each day. In this way, medieval almshouses addressed both longer-term care for residents and immediate relief for the destitute.

Importantly, almshouse benefactors were often motivated by religious duty and the medieval preoccupation with salvation. Founders established almshouses as chantries for their souls – endowing priests and requiring the resident “bedesmen” to pray for them in perpetuity. These institutions typically incorporated a chapel and daily religious routine. The very term “bede-house” reflects that residents were expected to say prayers (or “bedes”) on behalf of the founders. In return, the almsfolk received food, lodging and sometimes clothing or small stipends. By the late Middle Ages, England had a broad network of such charities – by the mid-1500s there were roughly 800 medieval hospitals and almshouses across the country forming a cornerstone of poor relief in an era with no state welfare.

Crown, Church and Charters

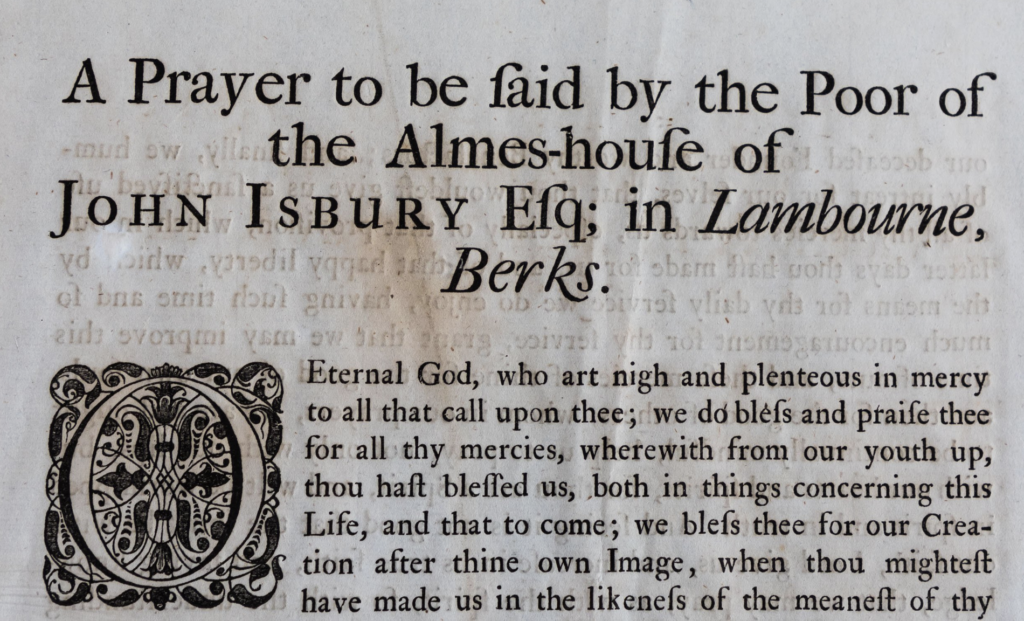

From the beginning, almshouses had close ties to both Crown and Church. Monarchs, bishops, and nobles alike acted as patrons. Kings and queens were among the benefactors – for instance, Henry VII granted a royal licence in 1502 to John Estbury to found a “perpetual chantry and almshouse” for ten poor men in Lambourn, Berkshire. Such letters patent were often legally required to establish an endowed charity, especially if land was to be given in mortmain (permanent charitable ownership). The Lambourn almshouse charter exemplifies the legal basis for many early almshouses: the Crown’s licence created a permanent charitable foundation, and the endowment of land provided income to support the residents. Founders also obtained confirmation from the Church, for example, the Hospital of St Cross was confirmed by Papal bulls in the 12th century, reflecting the Church’s blessing of its charitable purpose.

Ecclesiastical oversight was common: many almshouses were effectively church institutions, overseen by monastic orders or diocesan authorities. Before the Reformation, most were regarded as religious chantries because of their devotional obligations. The intertwining of charity and Church is evident in cases like St Cross, founded by a bishop and later augmented in 1445 by Cardinal Beaufort with a second almshouse known as the Almshouse of Noble Poverty. At St Cross, the two historic foundations still survive in merged form, and even today its brethren are distinguished as “Black Brothers” and “Red Brothers,” wearing robes of black or deep red in honor of the original 12th-century and 15th-century benefactors. This enduring pageantry underscores how closely tied to the Church and its traditions these institutions were.

Royal involvement was not limited to grants of permission; in some cases the Crown took a direct hand in charity. After the upheaval of the 1530s, when Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries and the subsequent Abolition of Chantries Acts (1545–1547) suppressed many religious foundations, almshouses that were purely chantries were dissolved and their assets seized. Nonetheless, the Crown sometimes re-founded or preserved certain charitable hospitals. For instance, King Henry VIII re-endowed St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London in 1546 (allowing it to continue as a medical charity), and later, King James I granted a royal charter to Thomas Sutton’s almshouse at the Charterhouse in 1611. Sutton, a wealthy commoner, purchased the former monastery of the London Charterhouse and endowed there “a school for the young and an almshouse for the old,” an act formalised by royal charter. This foundation, officially called “Sutton’s Hospital in Charterhouse,” became a model of a post-Reformation almshouse with Crown sanction. (It even prompted a famous legal case, The Case of Sutton’s Hospital (1612), which affirmed the rights of charitable corporations under English law.) In general, through the 16th and 17th centuries the legal basis of almshouses shifted from medieval ecclesiastical ordinances to charters, deeds and later statutory trust law – exemplified by the Elizabethan Poor Relief Act of 1601, which recognised the relief of the aged and poor as a charitable duty under secular law.

Life in the Almshouses: Rules and Routine

Life as an almshouse resident (often termed a “Brother” or “Sister,” or an almsman/almswoman) came with strict expectations. In exchange for a modest dwelling and upkeep, inhabitants were required to lead orderly, moral lives, usually under the supervision of a Master or Warden. Attendance at daily prayers was virtually mandatory. Many foundations stipulated that the brethren pray for the souls of the founder and attend chapel services every day. At the Lambourn almshouses, detailed rules drawn up by a 17th-century benefactor, Jacob Hardrett, required that almsmen be “of a humble spirit, fearing God and frequenting the Church” – in fact, each morning they were to confess their sins in their chamber and then spend an hour in prayer at St Katherine’s chapel, both morning and evening. Similarly, after Queen Elizabeth’s reorganization of John Estbury’s Lambourn charity, the ten resident almsmen had to be “poor men, humble in spirit and destitute, chaste in body, and reputed of honest conversation.” They were each provided with a gown (six ells of cloth every two years) and expected to attend chapel twice daily to say psalms and kneel around their benefactor’s tomb in prayer. These requirements illuminate the semi-monastic rhythm of almshouse life: part communal care, part religious observance.

Daily practicalities in historic almshouses varied by foundation. Most residents received an allowance in cash or in kind. In 15th-century Lambourn, John Roger’s will provided that each of his five almsmen be paid 8 pence per week, supplied with firewood, and given new clothes of Bruton russet cloth every third year. Food and drink might be provided at a common hall or individually. At Winchester’s St Cross, the medieval brethren dined in a hall and the foundation famously still offers the “Wayfarer’s Dole” – a tradition of giving any passing traveler a horn of beer and a piece of bread, dating back to its founding charter. Discipline was typically enforced by a Master (often a clergyman appointed by the founder or a patron). Misconduct or failing to observe the rules (for example, marriage, if the rules required celibacy, or persistent drunkenness) could lead to expulsion from the almshouse, as the charity was considered a privilege for the “deserving” poor. In appearance, residents were often identifiable by uniform dress. At St Cross, as noted, the Brothers to this day wear the distinctive gowns and badges of their respective foundations – a black robe with a Jerusalem cross for the original Order, and a claret-red robe with a Cardinal’s badge for the Beaufort-founded Order. Such customs reinforced the sense of community and loyalty to the benefactor. In essence, historical almshouses operated on a covenant: shelter and sustenance were provided for life, on condition that the almsfolk lived devoutly and obeyed the foundation’s ordinances.

Reformation, Decline and Revival

The 16th-century Reformation was a watershed for almshouses. Because so many medieval almshouses had been established as chantries or under monastic care, the dissolutions under Henry VIII and Edward VI led to the closure or repurposing of a great number. Endowments were confiscated or fell into lay hands. A contemporary report in 1548 lamented that “the relief of the poor” had been interrupted by the suppression of chantries. Some almshouses, however, managed to survive these reforms – often the smaller local ones that had no large assets or whose function was deemed purely charitable rather than spiritual. In Lambourn, for example, the chantry chapel attached to Estbury’s almshouse was dissolved in 1547, but the “poor men remained unmolested in their almshouses”. For a time the charity drifted without formal oversight, until Queen Elizabeth I ordered an inquiry in 1589. By examining the original deeds, the authorities reconstituted the governance of Lambourn’s almshouse, appointing the Warden of New College, Oxford as one trustee and a local gentleman as the other supervisor. This saved the charity and set new rules (as described above), ensuring its continuance. Such examples illustrate how, despite the Reformation’s shocks, the late 16th and early 17th centuries saw a revival and refounding of almshouses.

In fact, the later 1500s and early 1600s became a great age of almshouse (re)founding. With the monasteries gone, responsibility for the poor fell to parishes and private philanthropy. Tudor civic leaders and trade guilds stepped in to fill the void. Many livery companies in London, for instance, established almshouses for their decayed members in the late 16th century. (The legacy of this is still seen today in names like the Mercers’ Almshouses or the Carpenters’ Almshouses in London.) Notable Elizabethan-era foundations include the Lord Leycester Hospital in Warwick (1571) for aged soldiers and the Hospital of the Holy Trinity in Croydon (1596) founded by Archbishop John Whitgift. By the early Stuart period, wealthy individuals followed suit, Thomas Sutton’s Charterhouse (established 1611) being one of the most famous, providing housing for dozens of elderly gentlemen. These new almshouses often had royal patronage or charters, and they secularized the medieval model slightly: the focus shifted more squarely onto providing livelihoods for the “impotent poor” (aged or disabled) in line with the ideals of the 1601 Poor Law, rather than prayer for souls. But the ethos of Christian duty remained strong. As one scholar notes, many benefactors were driven both by compassion and by hope of “securing their own salvation” through good works. Almshouses continued to be founded throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, though the pace slowed as the statutory parish Poor Law system took on more of the burden for poor relief.

The Victorian Era and Almshouses Today

Almshouses saw a renewed surge of interest in the 19th century, during Britain’s Victorian age of philanthropy. Industrialization brought rapid urban growth and, with it, distressing housing conditions for the working poor. The grim reality of workhouses (the state-run poorhouses, especially after the New Poor Law of 1834) inspired some Victorians to create more humane alternatives. As a result, many new almshouses were endowed in the 1800s by industrialists, bankers, and urban benefactors. These tended to be built in towns and cities, often as picturesque rows of cottages or Gothic-revival courtyards that deliberately contrasted with workhouse barracks. It is estimated that roughly 30% of all almshouse charities in existence today were founded during the 19th century boom. By providing small self-contained homes (usually 6–12 units per site) for “respectable” local elderly, frequently with a pretty chapel and gardens, the Victorians ensured the almshouse tradition not only survived but expanded as part of the era’s broader charitable institutions. An example from this period is the rebuild of the Lambourn almshouses in 1827 by the Reverend Henry Hippisley, a local squire, who modernised the old buildings when they had fallen into disrepair. Across the country, similar restorations and new foundations were undertaken, many of which remain in use.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, England’s almshouses have continued to adapt, remaining a vital if small part of the social housing landscape. Today there are over 1,700 independent almshouse charities in the UK, providing homes for around 35,000 residents. These almshouses are almost all registered charities, regulated by the Charity Commission under schemes that dictate their governance, asset management and resident eligibility . A unique feature that has held constant is local management: almshouses are typically governed by volunteer trustees from the community, continuing the altruistic stewardship that has characterized almshouses “throughout the ages”. Funding for current almshouses usually comes from a mixture of sources. Many still rely on the historic endowments of land or investments left by their long-dead founders – for example, Lambourn’s John Estbury bequeathed farm and rental properties whose income still supports the almshouse centuries later. In addition, most almshouse charities fundraise or welcome donations and legacies to maintain their buildings and assist residents. Residents may pay a nominal weekly sum or “peppercorn rent,” but charges are kept very low to remain affordable. Notably, almshouse residents do not have the legal status of tenants – instead of a tenancy agreement, they have a licence to occupy, as beneficiaries of the charity. This arrangement harks back to the principle that living in an almshouse is receiving alms (charitable aid), not renting property on the open market.

Modern almshouses serve a range of target populations, but the focus is still on those in need – predominantly elderly people of limited means, often with a local connection or specific background the charity was set up to help. Some almshouses give preference to members of a trade (for instance, retired fishermen or guild members), or to local parishioners, or former employees of a particular firm, depending on the founder’s wishes. For example, the Charterhouse in London traditionally housed “gentlemen” who had fallen on hard times; today it welcomes both men and women over 60, drawn from various walks of life, who are in financial and social need. Daily life in contemporary almshouses is far less regimented than in centuries past, but many traditions persist. Residents often still call themselves “Brothers” or “Sisters” of their house, and chapels like those at the Charterhouse and St Cross continue to hold regular services for those who wish to attend. At the Hospital of St Cross, the centuries-old Wayfarer’s Dole of bread and ale is still ceremonially offered to visitors who request it – a humble reminder of the enduring spirit of charity. Meanwhile, the accommodation itself has been steadily upgraded. Many almshouses, though housed in ancient brick and stone buildings, have modern interiors with proper heating, bathrooms and kitchens, thanks to renovations that keep them “warm, comfortable homes” without losing their heritage character. Almshouse charities also innovate: in Lambourn today, the trustees are converting a disused chapel into nine new almshouse flats to meet local need, an “ambitious project” that shows the tradition is very much alive and forward-looking.

From their medieval inception as Christian havens for the poor, to their role in the patchwork of modern social housing, almshouses have shown remarkable continuity. They were born of the principle that a community should care for its weakest members, a principle championed by both Crown and Church in earlier times, and that principle survives, now carried on by charitable trusts and volunteers. Institutions like the Hospital of St Cross (often called “England’s oldest charitable institution”) and the London Charterhouse stand as living history, where one can still meet residents in ancient courtyards fulfilling the vision of their founders. In a BBC interview at St Cross, the Master observed that while the medieval custom of providing free lodging to wayfarers may no longer be routinely needed, the almshouse remains above all “a place of hospitality and welcome”. Indeed, the hospitable spirit of the almshouse offering dignity, community and shelter continues to bridge England’s past and present. Each almshouse, old or new, quietly tells a story of generosity and care that has survived a thousand years. As long as that story is honored, England’s almshouses will endure, adapting to whatever challenges the future brings while preserving their unique blend of history and charity.

Sources:

- British History Online – Victoria County History series (Hampshire and Berkshire volumes) (Hospitals: St Cross, near Winchester | British History Online) (Parishes: Lambourn | British History Online) (Parishes: Lambourn | British History Online)

- The Almshouse Association – History of Almshouses (History of almshouses | The Almshouse Association ) (History of almshouses | The Almshouse Association )

- Lambourn Almshouses (official site) – Our Story history page (Our Story – Lambourn Almshouses) (Our Story – Lambourn Almshouses) (Our Story – Lambourn Almshouses)

- The Charterhouse (London) – official history and Wikimedia images (London Charterhouse – Wikipedia) (File:London Charterhouse – Entrance from Charterhouse Square.jpg – Wikimedia Commons)

- Historic England & National Churches Trust – information on Hospital of St Cross (Hospital of St Cross, Winchester, Hampshire | Educational Images | Historic England) (Winchester Hospital of St Cross | National Churches Trust)

- London Charterhouse and Almshouse articles, Wikipedia (Almshouse – Wikipedia) (Almshouse – Wikipedia)